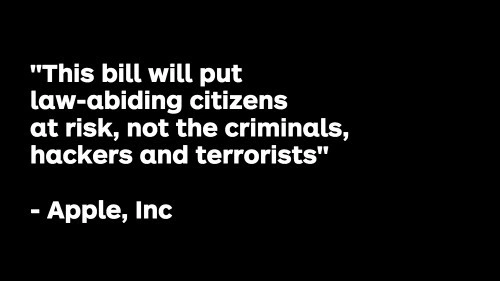

Despite protests from almost the entire Australian tech and start up community – and large swathes of the population – the Government and Opposition left us with perhaps the most Orwellian anti-encryption laws ever seen before they left for holidays. With Parliament set to resume, and Labor having promised to push for amendments, its critical this law is pared back to some semblance of balance.

For the moment, the law seems to be mostly focused on communications apps such as WhatsApp and iMessage. The argument has been made that law enforcement cannot do its job without being able to read the texts of suspects, but the vague wording of the legislation means it won’t end with messaging.

Even now, there is a battle brewing over whether Australia can have any end-to-end encryption services operating within its borders. The popular secure messaging service, Signal, is powered by open source code and as it stands it cannot comply with the law because it cannot provide a backdoor of any kind. Any attempt to do so would be immediately apparent to users, who would simply abandon the platform.

The only recourse is for Australia to ban the service, which in itself would be a technical challenge without something akin to “the Great Firewall of China”. Further, it is highly doubtful that Apple will make a special version of iMessage for Australia. It is more conceivable that Apple would simply strip iMessage from Australian iPhones – or stop selling them here altogether.

These laws put us in the same camp as not only China, but also Vietnam, who at the start of this year enacted sweeping cyber laws that in effect destroys their citizens right to privacy.

Encryption services developed in Australia, or those left doing business here, would likely be permanently blacklisted for being hopelessly compromised. This will not make Australia safer. It will simply leave us at a technological disadvantage that will make it unattractive for businesses, giving companies incentive to relocate.

The next step is to open up all computing interactions, not just messaging. Both Microsoft and Apple make operating systems that allow individuals to encrypt their files. As the legislation currently stands, systems like Dropbox, OneDrive, and iCloud Drive will be the next logical targets.

Businesses are already struggling to protect their data, and this will become even harder under the new legislation. Giving the Government a set of master keys means there is another entry point to your business that you don’t control.

The analogy does not do reality justice. Despite the language of the law, if the government is provided a way by the manufacturer to slip past encryption, it is a back door by definition – despite the mental gymnastics on display trying to call it anything other than a backdoor. It is a vulnerability and any vulnerability, no matter how well guarded, can be exploited.

When client data is breached as a direct result of weakened encryption, your clients will not blame the lawmakers. They will blame you. You alone are responsible for protecting the data with which you are entrusted, even if you are now forbidden to keep it behind an impenetrable lock.

Keep in mind the threshold for using these new powers is shockingly low. You only need to be under investigation for something that carries a penalty of three years in prison. That standard is trivially easy to meet. Remember, you may not be under investigation, but one of your clients, or former clients. Your innocence will not protect you from these new investigatory powers.

Not only are we looking down the barrel of scope creep and weakened defences, but Australian technology will become an international pariah. Right now, no one wants to be caught doing business with Huawei because the company is suspected of being a tool for the Chinese government.

Australia has just given international corporations and governments reason to quarantine our tech. There is no ambiguity here – no one needs to suspect Australia of drilling a peep hole into their in-country communications, the Government has proudly announced their intentions.

The next few years in Australia might well be the definitive business school course in unintended consequences. It is impossible to have a local tech scene if no one wants to buy what is produced here.

The practical effect of the law is to telegraph to the rest of the world that modern technology is not welcome here.

Australian businesses are entering a period when they will be viewed as moving in the opposite direction from the rest of the world. These are uncertain times that only future historians will be able to judge. But for now, the only certainty is that it is no longer business as usual in Australia.